Early Signs of Dementia Many People Don’t Recognize

Seeing the Small Stuff: Why Early Signals Matter (and Outline)

Not every misplaced key or hesitated word points to disease, yet patterns of cognitive and behavioral change deserve attention. Around the world, millions of families face questions about memory and functioning long before a formal diagnosis is made. The earliest phase is often quiet, more about inconsistent routines than dramatic symptoms. It’s the tiny stuff—Changes people often brush off—that can signal it is time to observe more carefully. Early recognition does not promise a cure, but it can support practical planning, safer choices, and access to evaluations that identify reversible contributors such as sleep problems, medication side effects, low mood, or nutritional gaps. Consider this article a careful map: we’ll distinguish ordinary aging from signs that interfere with daily life, illustrate how behavior can change before memory does, and offer ways to notice patterns without panic.

To orient your reading, here is the outline we will follow, with each section building on the last:

– Memory changes: what’s typical with age and what may be cause for concern

– Daily behavior: task management, social engagement, mood, and safety cues

– Early awareness: how to observe and document patterns without overreacting

– Practical steps: when and how to involve health professionals and loved ones

– Conclusion and next steps: moving forward with clarity and compassion

Why this matters now: the number of people living with cognitive disorders is expected to grow as populations age. Estimates suggest that a significant share of adults over 65 experience mild cognitive impairment, though many remain stable for years. Earlier conversations can reduce risk from financial errors, medication mix-ups, or unsafe driving, and they make room for preferences about living arrangements and support. This guide aims to be realistic rather than alarmist, giving you language and examples you can use today. Think of it as turning on a low, steady light in a dim room—enough to navigate without tripping, while you decide whether a brighter lamp is needed.

Memory Changes: From Normal Lapses to Concerning Patterns

Everyone forgets. Names slip, appointments blur, and that one word dances just out of reach. Normal aging commonly brings slower recall and the need for reminders, but information is usually retrieved later and routines remain intact. What deserves a closer look is not a single lapse but a pattern that disrupts daily life. The key questions are frequency, impact, and context: is the forgetfulness new, increasing, and interfering with independence?

Consider how typical changes differ from potentially concerning ones:

– Typical: occasionally losing track of where you left your wallet, then finding it after retracing steps.

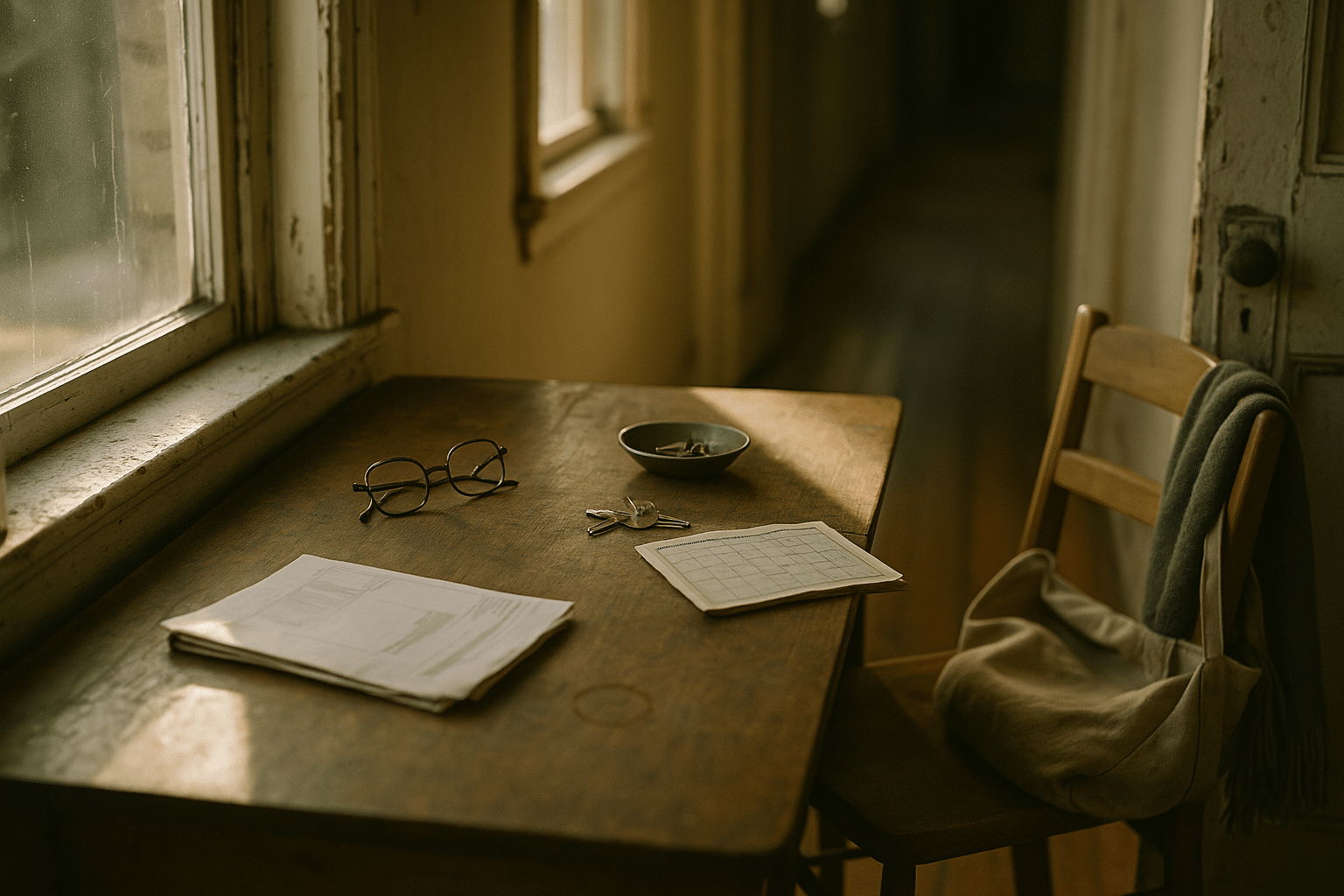

– Concerning: repeatedly placing essential items in highly unusual spots—keys in the fridge, bills in the laundry basket—and not remembering the sequence of events that led there.

– Typical: needing a list at the store but shopping successfully.

– Concerning: abandoning a familiar shopping trip because the steps feel confusing, or buying duplicates over and over without recall of previous purchases.

– Typical: sometimes struggling for a word, especially under stress.

– Concerning: persistent word-finding difficulty that leads to vague speech, frequent substitutions, or trouble following a simple conversation.

Short-term memory—the ability to form and retrieve recent memories—is often affected first. Repeatedly asking the same question within minutes, missing important dates despite reminders, or forgetting recent conversations may signal more than ordinary aging. Another early clue is prospective memory, the ability to remember to do something in the future, such as taking medicine at a set time. If timers and calendars no longer help as they once did, note when that change began and how consistently it occurs. Estimates vary by study, but many clinicians observe that mild memory issues can remain stable, improve if related to treatable conditions, or progress to more significant impairment over several years. What you can do now: keep a simple log of slips that genuinely change routines; bring it to a primary care visit for perspective. A short, factual record often reveals whether a few scattered lapses are just noise—or part of a meaningful pattern.

Daily Behavior: Subtle Shifts in Routine and Social Interaction

Memory is only part of the early picture. Everyday behavior often changes first in quiet ways: bills go unpaid, favorite recipes need step-by-step prompting, or a once-reliable driver starts avoiding left turns and unfamiliar routes. These shifts reflect planning, attention, and judgment—skills that depend on multiple brain systems. Watch for Behaviors that raise questions, especially if they represent a clear departure from a person’s lifelong habits and values.

Practical signals to monitor include:

– Money management: late fees, unusual purchases, or falling for phone scams that previously raised instant skepticism.

– Household tasks: repeated half-finished chores, leaving burners on, or difficulty sequencing a familiar recipe.

– Work and hobbies: reduced participation, missed deadlines, or abandoning projects that were once a source of pride.

– Social patterns: withdrawing from clubs, repeating stories several times in one gathering, or growing tense in noisy environments that never used to overwhelm.

– Mood and personality: more irritability, anxiety about routine tasks, or apathy toward activities that used to motivate.

– Orientation and navigation: getting lost on a well-known route, especially without an obvious external cause such as construction.

Importantly, context matters. A stressful life event, grief, poor sleep, or a new medication can explain temporary dips in attention and motivation. Sudden changes—overnight confusion, disorientation, or severe behavioral shifts—warrant urgent medical attention because infection, metabolic imbalance, or medication interactions can be responsible. Gradual changes, in contrast, call for consistent observation. Write down the date, the activity, and what made the behavior stand out. Over a few weeks, a pattern may emerge that helps a clinician distinguish age-expected variability from something that needs deeper evaluation. Families often find that adding small supports—automatic bill pay, pill organizers, and simplified routines—reduces risk while they seek advice. The goal is not to label too early but to protect independence while gathering facts.

Early Awareness: Observing Without Alarm and Acting With Care

Early awareness is a habit, not a single decision. It means noticing, documenting, and gently testing whether supports restore function. Think of it as a home safety check for the mind—practical, respectful, and repeatable. Start by making the environment friendlier to memory and attention, because improvements after small changes often reveal whether a problem is fixed by structure or needs medical input. Examples include setting consistent meal and sleep schedules, anchoring keys and wallets to one visible spot, and using a large wall calendar that everyone updates daily. If those adjustments reduce errors, great—keep them. If the same mistakes persist, that is useful information to bring to a clinician.

Here are simple ways to build early awareness:

– Keep a brief daily log: one or two lines about notable memory slips or task difficulties, including time of day and triggers like fatigue.

– Run small experiments: try a checklist for cooking or a phone alarm for medications and note whether performance improves.

– Invite another perspective: a trusted friend may notice changes you miss; balanced input helps avoid both denial and overreaction.

– Schedule a health review: ask about hearing, vision, sleep quality, mood, and medications—common, treatable factors that affect cognition.

– Plan for safety: consider removing driving at night, consolidating finances, or using automatic shutoffs for appliances while you gather more data.

Many adults over 65 experience milder cognitive changes that never progress to dementia, while a portion do move from subtle impairment to more significant difficulty over time. Because trajectories vary, the first mission is to understand the individual’s baseline and trend. If concerns persist, primary care can administer brief cognitive screenings and decide whether to refer for neurocognitive testing. Results are pieces of a larger puzzle that includes medical history, daily functioning, and personal goals. Early, steady attention narrows uncertainty, allows time to plan, and keeps the conversation grounded in what matters most: comfort, autonomy, and safety.

Conclusion and Next Steps: Turning Noticing Into Support

Early recognition is less about labels and more about choices. By the time a diagnosis is clear, families that kept notes, adjusted routines, and asked for guidance often feel more prepared and less rushed. That preparation starts from a simple truth: Why awareness starts with noticing. Notice what changes, when it changes, and how supports help or do not help. Then act in measured steps that protect independence while reducing risk.

Here is a practical path forward you can tailor to your situation:

– Start a two-week observation period: record memory slips, behavioral changes, and any fixes you try.

– Share the log with a clinician: ask about sleep, mood, pain, medications, hydration, hearing, and vision.

– Add low-burden supports: pill organizers, calendar routines, one-spot storage for essentials, and simplified finances.

– Talk openly with trusted people: agree on signs that would prompt a follow-up visit or safety change.

– Reassess monthly: if patterns stabilize or improve, maintain supports; if they worsen, request further evaluation.

For those supporting a spouse, parent, or friend, remember that clarity often builds slowly. Aim for compassion over perfection and safety over pride. Small steps—arranging a medication review, riding along to observe driving, or simplifying meal prep—can meaningfully reduce risk while preserving dignity. If you are the one experiencing changes, know that asking for a checkup is an act of agency. The earlier you understand what is happening, the more influence you have over future decisions about home, work, and community engagement. The goal is not to fear every lapse, but to cultivate steady awareness, gather facts, and choose supports that fit the person—not the other way around.